Notes on the paintings of Uta Peyrer

Could it not be that we are inventing our intuitions of time and space just as much, or as little as we invent everything else in our life?

Of course we are born into a world, which appears to be always and already, ready made. It is such a demanding task to recognise this illusion and perhaps even a greater demand is the demand to respond to this challenge in a world, which is no longer, we are called to invent a world, which is not yet. A world which may well never was, or never will be and yet this, our own created illusion, seems to determine it in any number, or versions, of any given reality. In another words: we are doing away with so many illusions only to replace them with our own, deeply subjective version. Indeed, could the world be reduced to one version or the other? This world will be seen in as much versions as we are capable to create. This is the principle reason of the hysteria of painting. It is when reason is suspended in order to create the elbowroom for a supreme suspense of all practical judgment.

In the 26th chapter of Chuang Tzu it is written: "A basket-trap is for holding fish; but when one has got the fish, one need think no more about the basket. A foot-trap is for holding hares; but when one has got the hare one need think no more about the trap. Words are for holding ideas; but when one has got the idea, one need think no more about the words. If only I could find someone who has stopped thinking about words and have him with me to talk to". (In Arthur Waley, Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China). Thus the pictorial fact constituted by infinite moves which allow in their interactive combination, movements and materials, to produce the tactile reality of paint, brush strokes, transparencies, the subtle play of opacity and resistance. But, since seeing amounts to another creation, it may be compared only to the idea in relation to the words. We are constantly urged, gently with a smile and a kind invitation to reconsider, to throwaway our averted gaze, and to embrace something, which exists nowhere else, which will never be the same, as if we are moving in parallel universes. The movement of the natural light is already such a trajectory. It will never shine again on the same spot. At the same time, at the same angle. Rarely have we been made to feel so acutely the transitory character of our life on earth as in these paintings. Their solid manifestation itself negates a desire for permanence. Ever since the Egyptian Coptic portraits were painted in Fayum in late antiquity, there is in European art that thread of other worldliness that cannot be evoked well than as in St. Augustine's mother Monica, in what is called Monica's Vision. Monica was ill, very ill.

St. Augustine and his mother were waiting in Ostia for the boat, which was to carry her back to her home in Carthage. But, there was a delay, and one day as they were looking together at the garden through the window, Monica said that if she was traveling to where she thought she was traveling to, then she did not need a boat. And St. Augustin tells us that following these words they were looking at the garden and they saw that "what is, is". Michael Tippetts wrote his "Monica's vision" with St Augustine's memorable words.

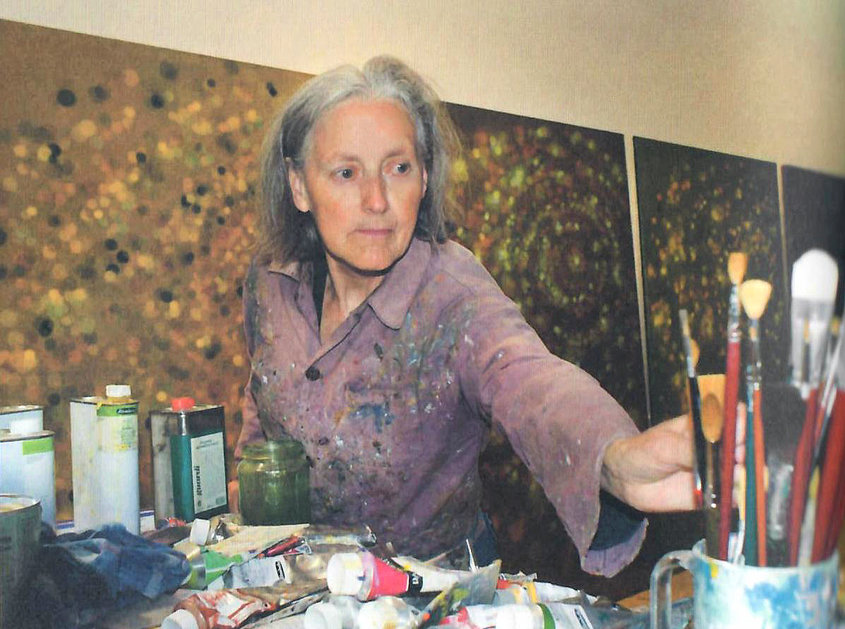

The miracle in these paintings is that Uta Peyrer who was born in the Burgenland to a family that hailed from Salzburg and the Wachau Valley along the Danube, has been so completely converted to this version of reality which she has made so much her own that we can no longer remember that she has never attended an art school or any other 'institution of higher learning'.

We can no longer even associate her with all the other artistic expressions, which could have been of help to her, and perhaps were of untold help. The great voyages to Japan, the Middle East, Eastern Europe and Norway for example. Not to mention a good period of working in down town New York in the seventies. Agnes Martin and her mentor Ad Reinhardt come to mind, but only to be forgotten completely as you contemplate Uta Peyrer's paintings. The singularity of this endless repetition of her repertoire constitutes a field of time that is entirely her own. A Fiat lux of an instant revelation, a manifold of possible temporality strikes the canvas and disappears again only to reappear in another guise, as a canvas with its unique configuration. She has reached out to so many other languages only to discover her own. Indeed, we are put to the task of deciphering that which can only remain silent and, in almost Keatsian fashion, this makes the sounds of the unuttered words even more sweet.

No matter how symbolic are the round and oval forms, no matter how like constellations in heaven are her compositions, they seize us by their symmetry, the constant iteration of proportions between parts and side and the ever present harmonious and regular flows of marks on her canvases. They offer us a parallel universe. Her universe is one in which pain and pleasure are cut from the same piece of cloth. Her brush strokes weave a tapestry of shimmering colors singing with a mantra of rhythms both tonal and atonal the glory of all there is.

When we look, it cannot be seen - it is beyond form. When we listen, it cannot be heard - it is beyond sound. We try to grasp, it cannot be held - it is intangible. The Tao teaches us that these three are indefinable, therefore they are joined in one. Neither bright nor dark, an unbroken thread beyond description, the form of the formless, the image of the imageless, it is called indefinable and sometime beyond imagination. If you will look for the beginning there will be no beginning, when you will follow it there will be no end. We are moved to move with the present. The painter can wait quietly while the noise settles, she can remain still, hours, days, weeks, months, years until the moment of action. In fact, she seeks no fulfillment. Not seeking fulfilment she is not swayed by desire for change. Uta Peyrer gives us the gift of subtle, mysterious, profound, responsive in which the depth of knowledge unfathomable is incommunicable. Therefore all she can do is describe their appearance.

Yehuda E. Safran, 21st of October 2008, New York

Points and Moments in Time

For several decades, Uta Peyrer has consistently followed in the tracks of her work as an artist. Entangled in a life of solidarity devoted to numerous tasks and requirements and right from the center of time, she has continuously attempted to increase the visibility and profoundness of her traces. The viewer is, thus confronted with an artistic career that gradually unfolds from picture to picture and has certainly not only resulted from exercises in form or in criteria inherent to art, but also has to do with life as such and a realm of experience from which the artist gains her powerful insights and which is in tum elucidated by her pictures.

Familiar with the sensual Catholicism of the Austrian Baroque (which still constitutes a major impulse) through her origins, she started out from this very comer of the world to also appropriate non-European and primarily Asian aspects of spirituality, as is reflected in such work titles as Prayer (1958), Shinto Gate (1970), Five Spirals (1975), or Saturated Time (1985/86). This last title, paraphrasing the old experience of kairos, the supreme moment, alludes to various cultural associations in a particularly telling fashion. For when elapsing time seems to stand still, gaining permanence or even eternity in a blissful moment - when time has become saturated and well rounded - then one can grasp with one's senses what otherwise merely appears as a vague hope or empty phrase. Is one wrong in assuming that Uta Peyrer's work can be seen from such a perspective? In terms of structure, even her early pictures attest to the circumnavigation of an open center, the search for a stabile focus, for tranquility amidst turbulence, in the course of which the paths of one's experience converge and gain ground. After all, a point emphasized - particularly a centered point - is a primordial symbol of concentration and the human self in which diverging ambitions and emotions combine and come to rest. If the point has become the essential formal element of these paintings, this certainly has not happened purely for the sake of abstract language. These early pictures' structure recalls, among other things, the ritualistic repetitions of the rosary, a prayer formula recited time and again. Basically, this structure relates to the tranquility and cyclic contemplation during which beholders of the world recollect themselves and take an inward tum, encountering something fundamentally different that cannot be rendered by an image and which may, if at all, be represented only through a symbol in the sense of a point that stands for condensed concentration.

Foundations on which this oeuvre is built in terms of culture and practical life, no mention has yet been made of a new beginning. It has to do with the craftsmanship or manual aspect of painting, as well as with insights gained by the avant-garde that started to develop in the late nineteenth century. In the context of the point, two positions naturally suggest themselves: one proposed by Seurat and another propagated by Kandinsky (which was also put down in writing in Point and Line to Plane in 1926). In view of these pictures, the association with Seurat cannot be entirely wrong, since he was the first to seriously implement the realization that the point as a primordial element that had already been discussed by the artists of the Renaissance was now the only element that mattered. Seurat realized that everything we perceive could be turned into an image through the pre-representational vehicle of the point. Whatever we recognize in his paintings, be it a nude, a circus rider, or a landscape: it owes its existence to diffuse and dispersed matter, formed by an assemblage of points or dots whose color, opaqueness, and transparency the artist raised to the status of language. Kandinsky eventually elaborated on this thought in his world of pure abstraction. The distribution of points or dots has turned out to be a method of adding effects, associations, and meanings, with the point being a carrier of possible content.

The question whether Uta Peyrer has actually sought to literally refer to these theories is not decisive. In any case, she moves within the periphery of such thinking and pictorial possibilities. Her work differs from Kandinsky's insofar as it relies on color to a larger degree, using the anonymous vehicle of small colored "discs" of various dimensions and density. However, an element by itself does not yet make a picture, as little as the mere accumulation of such elements proves to be sufficient. What is essential is to connect them meaningfully so as to create a picture. This meaning reveals itself as soon as one considers how these colored points relate to each other and to the picture plane. They threaten to dissolve and get lost, yet they simultaneously take on shape, gaining in clarity and contrast. If nothing else, these processes, with their intricacies, ambiguities, and concentration on several focuses, expose the nature of the medium by which a "picture" is defined here. It is a colored medium that may be described as semitransparent, dim, or hazy, for it equally lends itself to concealing the points and emphasizing them, thereby creating a homogeneous atmosphere, an infinite colored space, between their virtual movements and contrasts. The effects produced by this atmosphere, the nuances of color by which it is defined, number among the innate qualities of these paintings. In entitling her works Red Space, Golden Space, or Temporal Processes into Lightness, Uta Peyrer provides us with some clues as to the contents and meanings of these spheres of color.

The artist plays with different degrees of saturation and with the color contrasts among the individual dots and between them and the background, as well as with various forms of overlays and overlaps. Coronas. auras, and comet tails emerge and integrate the points and dots within the medium of color. An impressive space takes shape that only manifests itself when we look at it, although we never succeed in penetrating or conquering it. It provokes such cosmic associations as the Milky Way or the firmament proper (which find direct expression in titles like Evening Star, a work dating from 1985-88), but relates to a cosmos that does not exclude the spectator's emotional and spiritual inner world. A picture's space always represents an aspect of time, too. We keep failing to fixate our gaze permanently on an individual dot; this virtual movement help struture the picture's sequence and rhythm, but it also contributes to the formation of unstable places in this infinite space. These paintings convey an experience of flotation (its first and dominant impression) in which our ability of localization is reversed: the order of temporal sequence and spatial succession merge to form a metaphor for totality and an all-encompassing unity.

These pictures neither describe astronomical events nor merely depict emotional constellations. Their achievement lies in a synthesis. For the point that attracts our attention and seeks to structure, irritate, and stabilize is both a motif symbolizing our mental and emotional concentration (something inside ourselves) and a geometric form (something outside ourselves). The colorful metaphors we perceive are thus always a cosmos of "stars and feelings", of interior and exterior views. The color processes are always also the processes of the mind: the mind that experiences and comprehends them. It is for the spectator to experiences the movements of dispersion and concentration, of ascent and descent, and of removal and approximation when confronted with these pictures. In the course of her development, the artist has come to conceive these pictorial processes in a more open fashion: several relative centers compete with one another, hierarchies are avoided, and a picture's focus is no longer predetermined, but remains to be identified by the spectator in a never-ending task. In this sense, Uta Peyrer's paintings represent neither mere abstract situations nor pur visualprocesses. They take into account the spectator's participation. This is about experiences that derive from a reality and from the cherished habit of introspection, from the exploration of one's own feelings. Ideas, yearnings and visions. Nonetheless, this art also deals with the concrete world in which the reality of the leaf on a tree and of the face in front of us (our own mirror image) is not limited to their existence of being things, but equally encompasses the forces that emanate from them. Uta Peyrer's pictures testify to these forces’ sensual diversity and impressive intensity.

Gottfried Boehm, Basel

UTA PEYRER - KARL PRANTL Miroslava Hajek

The titel's name was borrowed from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's novel Die Wahlverwandtschaften, which used the concept of affinity (the novel's title can also be translated as "elective affinities"), as an organizational metaphor for marriage and for the conflict between responsibility and passion. This concept of elective affinities is based on the older concept of chemical affinity, which can be defined as the characteristic that enables chemical substances, under certain circumstances, to form compounds. Applied to the visual arts, we arrive at three factors: two independent factors and a third one resulting from the final outcome of the mutual interaction of the first two.

In our case, the concept of affinity forms the starting point for an exploration of a phenomenon that appeared over the course of the twentieth century - the artistic work and shared life of artistic couples. These unions have enriched our culture in general and brought a new and mutual sensitivity that in many cases enabled women to participate in an art scene from which they had previously been excluded.

Renowned Austrian artists Uta Peyrer and Karl Prantl are one such couple. Their work first became known to the interested Czech public in the 1960s. The art of the recently deceased Prantl in particular has had a positive influence on many sculptors - not just through the character of his work, but also thanks to his groundbreaking initiatives such as his founding of several sculptural symposia to which Czech and Slovak artists working with classic sculptural material (stone) were invited as well. Peyrer's work - paintings with an intense focus on the individual's relationship to the cosmos - also exhibits an affinity to certain Czech artists who found themselves attracted to a similar artistic orientation in the 1960s.

Our aim was to explore the basic shared concepts that formed these two artists' aesthetic and philosophical approach, to compare their artistic processes and development, and to identify the mutual influences that were a natural result of their life together.

In our confrontation of these two artists, we explore the creative expression of similar artistic orientations, realized in such different media as painting and stone sculpture. We identify the themes that, both independently and in parallel, developed on both sides in order to result in remarkable artistic outcomes.

The exhibition was designed as a synthesizing walk through the artists' lives. Its aim was to depict and emphasize the dialog that formed between their works during their long life together, all within a historical context that underscores the timeless nature of their work. The suggestive interior spaces of Klenova Castle offer a view into seven rooms representing seven situations, seven symbolic moments during which the viewer may sense the artists' aesthetic as well as human kinship. Each room underscores not only the affinity of their artistic expression and the way in which they translate universal questions into the language of art, but also presents the personal, private, and creative spaces that each artist developed independently. Despite their clear aesthetic harmony, both artists' works show a strong and autonomous individuality.

The selected works emphasize the important bond that connects the two artists' work. First and foremost, this bond consists in their search for and expression of a new spirituality that extends beyond the limits of the human senses and human understanding.

This unique confrontation of their works and personalities allows us to better understand their independent artistic efforts as well.

At a time when the pace of life inexorably increased and grew more frantic, Prantl chose to express his aesthetic ideas and to realize his sculptures using stone - a material that requires lengthy and exhausting work by hand. Prantl's works evoke a sense of eternal life unhindered by human concepts of space and time.

Already by the late 1950s, Prantl's sculptures - most of which he had begun calling Stones for Meditations (Stein zur Meditation) - had crystallized into geometric structures, though these were never as precise as mechanically worked stones. The surfaces of his geometric bodies, treated with grooves and furrows, tremble with an inner tension. We frequently encounter the motif of one or several rounded pits worked into the stone. In some cases, these perforate all the way through the stone; especially in his large-scale sculptures, the mass of the stone reinterprets outer space within inner space. Prantl shows an ever-increasing interest in the inner life of matter. The outlines of his sculptures - cubes, spheres, or parallelograms - become irregular, with the stone's veins following along a series of indentations. Later, the veins churn up the surface of the stone, and it is as if we can see and feel its pulse.

Roughly until the beginning of the 1980s, Prantl works with monochrome material, primarily white marble and black granite. For his sculptures marked by stone veins, he likes to use serpentine. At the turn of the sixties and seventies, he creates a series of hermetic black granite monoliths of varying sizes. These perfectly smoothed objects, sometimes with only a minimum of surface working, create a strong emotional experience, as if they had accumulated the energy of the universe.

In order to properly understand Prantl's creative process, we must understand his relationship to nature. Prantl feels himself to be a part of nature, its anonymous tool. The act of sculpting stone merely reveals what was hidden inside. With time, he lays bare not only the stone's veins, but also its bones.

Prantl succeeded in combining the painterly quality of spotted granite with a living structure that feels as if it were frozen, spellbound, in petrified ice. Equally impressive are his sculptures made using greenish-red Ussuriysk amazonite. In places, the uniform green, dotted mass is suffused with a red color as if it were soaked in blood. Prantl succeeds in mastering the stone's dramatic character without exaggerating its natural pathos.

Although Karl's stones seem to live their own life, they are immersed in a deep inner silence. By comparison, the swirling colors of Uta's paintings bring to mind a musical atmosphere projected into infinity by light.

Eventually, Peyrer's different approach to the meaning of color meets up with Prantl's search for and discovery of color in his stone sculptures. Uta uses layers of pigment to create vibrating round surfaces that give the illusion of a lucid, eternally expanding space. For Prantl, color is a tool for expressing and depicting the eternal inner space that he sought within the microcosm of his stone material - primarily granite and, during the last phase of his life, Norwegian Labrador - which he succeeded in working in such a manner as to emphasize the optic qualities of its shimmering interior.

Both artists express the ideal of a new and abstract spirituality using spherical shapes. In Uta's paintings, a cluster of spheres forms a colorful nebula that reminds us of the depths of the cosmos, while Karl's sculptures contain chains of spheres reminiscent of living veins - sometimes only hinted at - spreading out beneath the stone's "skin.”

Prantl presents us with his view of life within the broadest meaning of the word, connected by organic and inorganic elements.

One particular theme shared by the work of both Peyrer and Prantl is their extraordinary relationship to time, which they understand as continuous, without beginning and end, where the most important thing is to reveal the essence of being. Nevertheless, the dominant theme in Uta's paintings is the depiction of space through the use of colors; time is present in a more conceptual sense.

In his text for the exhibition catalog to Peyrer's exhibition "Expanding Space and Stretching Time," professor Herbert Muck offered a fitting description of the concepts of space and time in her work.

"She constantly returns to paintings she has begun. Large fields, composed of point centres, are extremely sensitive to even the smallest disturbances. Changes mean, that everything must be integrated again on the basis of a single impulse. With fine, transparent brushstrokes, another thin layer of paint is applied, and a new nuance changes the painting. Those intermediary results can be modulated further. It could be said that the painter risks taking new steps in order to keep the whole in motion, to renew the tension. She says: "I risk freedom". Often a painting will remain unchanged for several months, and she will spend hours in front of it before she decides to take the next step. Into these paintings of cosmic creation and metamorphosis are woven the phases of life, periods of existence in which Uta herself undergoes the processes of creation and extinction, which allow a work to come into existence and change".

Peyrer's exploration of chromatic effects places her work alongside that of other international artists who focused on this issue, primarily in the 1960s and '70s. This period was marked by a prevailingly rational or even scientific approach (op-art), with many artists searching for controllable possibilities for the use of color balance, experimenting with optical effects, and trying to create the illusion of perspective by merely approximating various colors, thus revealing so-called retinal colors, which are formed directly in the eye without existing in real life. Uta applies this knowledge instinctively, and succeeds in overcoming the limits of rational understanding, which in a certain sense limit painting. The spaces in Uta's paintings contain the strength of cosmic magnetism, and even appear capable of giving us an impression of its sound.

Uta Peyrer's paintings are music translated into color. They remind us of colorful musical scores. Her work follows in the footsteps of the Orphic paintings of the early abstractionists such as Frantisek Kupka or Sonia and Robert Delaunay. Nevertheless, we can find a greater connection, perhaps unconscious, with the paintings of Romolo Romani (1884-1916), which depict drops falling onto a watery surface and in which we may hear rhythmic sounds. The musicality of Uta's paintings is rhythmic as well; we can almost hear it, especially in the room dedicated to Steve Reich.

The multifaceted realities of the universes explored and discovered in the art of these two artists are different, but closely related. Karl Prantl reveals the spirituality of infinite matter, while Uta Peyrer reveals the spirituality of infinite space.

I am convinced that the exhibited works give a clear insight into how they supplement one another and how many new ideas were born during the artists' life together. As a result, we understand how important it is, if we want to understand various artistic languages, to be aware of the web of contexts and interrelations, to understand its logic, and to classify it within the general history of art.

Herbert Muck, Cosmological Space-Time Pictures, Uta Peyrer catalog, CMVU, Praha 2006